Patterns and Motifs

Patterns and Motifs

Riza Quli Khan Hidayat was a 19th century Persian writer who, in his travels, he mapped the path of the Oxus river that brought cultivation in the steppes and wrote, “During winters, the river is frozen over, allowing caravans to pass over it, while the water flows beneath the ice” (Khazeni 2010, 599).

Along the Silk Roads, oasis towns typically served as centres of exchange where travellers, pilgrims, and settlers would coexist, trade and sometimes adopt artistic styles and practises from one another (Khazeni 2010, 604). This first-hand historical evidence serves the purpose of encapsulating the dynamics of exchanges along the Silk Roads and further, opens up the discussion for how more than just material items were exchanged but also ideological, symbolic, and cultural meanings were simultaneously adopted in these encounters. Within these exchanges, I argue that patterns and motifs were perhaps some of the most physically noticeable shared items among cultures, peoples and religions.

The Pomegranate: Health, Fertility and Resurrection.

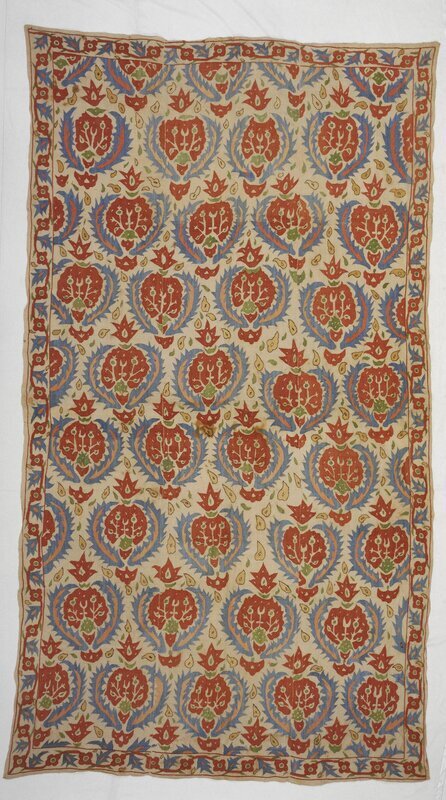

The Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition titled “An Enduring Motif: The Pomegranate in Textiles” outlined the popular depictions of the fruit with its origins tracing back to Persia thousands of years ago. In this exhibit, the pomegranate is acknowledged as a fruit symbolizing health, fertility and resurrection (Blum et al.). It highlights the different depictions of the fruit, whether through art, textiles, poetry or use of the physical fruit amongst different cultures. Alternatively, in Islamic legends the pomegranate’s seeds are each a gift descended from Paradise. (Blum et al.)

In John Gillow’s findings, Tajikistan textiles, especially prayer cloths depicting a “Mihrab” (an arched wall in a Mosque pointing to the direction of Mecca) often used the pomegranate motif to symbolize happiness and fertility (Gillow 2010, 212). In these representations, the pomegranate is illustrated as a flat circle, given the illusion of pointed ends through the surrounding vine-like motifs and the stem typically placed at the bottom. The enduring presence of the pomegranate amongst cultures both within and outside of the Islamic world represent a notion of shared ideologies. The purpose of identifying these separate depictions of the pomegranate is to illustrate the enduring symbolism of the fruit throughout time and space where, even if adopted from another culture, the motif then becomes constructed with its own meaning in a new cultural context.

The Garden of Paradise / Jannat

“Then as to those who believed and did good, they shall be made happy in a beautiful garden.(30:15)”

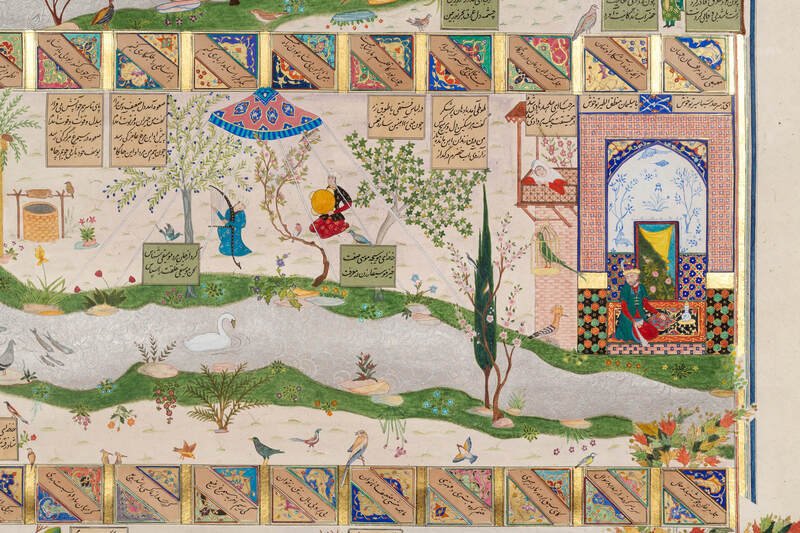

In Islam, Jannah or, the “Garden of Paradise” is a final place of eternal rest and peace, where the faithful and righteous followers of Islam are rewarded for their efforts (Currim 2012, 8). After the British invasion of the Mughal empire in India, the once prominent palace gardens that were constructed to mimic Jannah were abandoned and no longer treated as flourishing spaces. (Currim 2012, 17) Instead, depictions of Jannah remained alive through artists who took to representing the “Garden of Paradise” through poems, art, and textiles often using natural elements such as roses, pomegranates, hyacinths and vines to symbolize the beauty of the promised Garden.

For instance, the palmette motif resembles a fanned flower, argued by scholars to be either a vertically-cut lotus or peony with a split leaf (Spuhler 2020, 98). The palmette motif is not exclusive to a singular culture or religion and has roots in Ancient Babylonian, Greco-Roman and Byzantine periods where the pattern first existed as a more simplified fanned decorative piece. Within these cultures, the symbol was said to evoke the images of a “paradisiacal garden” where the motifs were intentionally drawn with unnatural features to suggest that the garden of Paradise would feature natural elements unlike any worldly plant (Spuhler 2020, 98).

The traditional elements of Jannah, as found in the Qur’an depict the Gardens as filled with trees, fruits, running water, and four rivers of milk, honey, water and pure wine (Currim 2012, 9). The four rivers split the gardens into four separate gardens and perhaps it is no coincidence that the robe too, is split up by four distinct tales - each containing a paradisiacal story of their own. The practice of recreating paradise therefore, in nature, poetry and textiles, were utilized by artists to convey the constant reminder of the pleasures and promises of Jannat or, paradise (Currim 2012, 17).

By examining the motifs of the robe, that is, the repeated patterns and icons embedded with symbolic meanings, we can further conceptualize the binding components of the seemingly unrelated stories of the robe. The Aga Khan Centre’s exhibit titled, “Islamic Paradise Gardens and the Garden Within” provides an additional definition for the term Jannat, which aside from “garden”, also means “enclosed by walls” (Clark 2021). For the AKM robe, I imagine the promise of Jannat to be the binding concept of the four stories that within a realm of the unimaginable divine remains four unique tales across time and space, each provided a haven by the garden enclosure so that their stories may continue to exist across time and space.